The Night My Life Changed for Ever

My life changed during the night of October 29, 1947, as my boss, Mr. Hodess, and I sat in front of the teleprinter at 77 Great Russell Street, the offices of the Jewish Agency for Palestine in London. One by one, the votes that would decide whether a Jewish State was to be born rattled noisily and alphabetically on to the long streamer of the teleprinter. Afghanistan - No. Argentina – abstain. Our hearts sank. But then: Australia – yes, Belgium - yes, Bolivia – yes, until by 1am we knew that the Security Council had agreed, by 33 votes to 13 with 10 abstentions and one absentee, to partition Palestine. The State of Israel was finally, finally to be born and we were jubilant. The phones began to ring, colleagues rushed in and even in the normally strictly tea-drinking setting of the Jewish Agency someone produced a bottle of champagne.

I was a junior correspondent of Palcor then, the Palestine Correspondence Agency, which after May 1948 became Itim, the official news agency of the new State. It had been my task until then to follow the endless Palestine debates in both Houses of Parliament, and to listen and transcribe the unremittingly hostile and pro-Arab pronouncements of the Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin. But on that night, Bevin lost his sting, his views were overruled and we were euphoric.

At last I could reassure my parents that I would no longer need to immigrate illegally, and eventually got their reluctant agreement. My bags were packed and I left for my new life in the State of Israel on August 8, 1948.

There are so many memories when I think of those first two years in Israel that it is hard to know which to choose. But perhaps the first that represents the spirit of that time is how I found a place to live.

I arrived in Tel Aviv with very little money and nowhere to stay. Apart from the knowledge that I had a job waiting at the Government Press Office, I had no contacts other than a letter of introduction to someone called Cilla in Frug Street, Tel Aviv. I rang her bell unannounced and was made to feel welcome immediately.

After a very short time, Cilla asked if I had somewhere to stay and when I said I had not yet started to look, she quite simply said, "Why don't you stay here?" She was due to go quite soon to Cyprus for some months and said that I would be very welcome to stay in the flat while she was away. It was as simple as that. There were no hesitations, no suspicions, no references needed, not even – as far as I remember – any rent required; just total trust and friendship towards a new arrival.

I was indeed very lucky. But while the circumstances and the unexpected comfort were unusual, the spirit of hospitality was not. As I am sure, some of you will remember that the Yishuv at that time felt like one large family where the little that was available was shared and where every chair or sofa could serve as a spare bed for expected – or even unexpected - visitors. This was a time of togetherness, of reaching out, a time when the collective was more important than the individual and when there was one goal for all: the war had to be won and the new State of Israel had to be made secure.

Work was hard but exciting. From being a very junior reporter in London, I was suddenly in a beehive of activity and expected to work like a real journalist. Israel was big news in 1948 and the Public Information Office, the P.I.O. as it was known, was home for the whole foreign press corps. Censorship was strict, and although we were frequently bussed to within strategic distance of various operational zones, we had to rely largely on the bulletins and press conferences held by Moish Pearlman, the official spokesman.

The nearest I came to live action was one day on the roof of the G.P.O. building in Jerusalem, off Mamilla Street, shortly after the newly-built Burma Road was opened and food and supplies could once more be transported to beleaguered Jerusalem. From the post office roof, one could see across into the Jordanian-held Old City but when I foolishly looked over the parapet of the post office building, the bullets started to fly from the city wall which was solidly manned by snipers. I was smartly pulled down to lie flat on the roof and got a good telling-off once we had crawled to the stairs and were safely back in Mamilla Street.

By the end of October 1948, the war was almost over and tiny Israel had miraculously defeated five Arab armies. But before that there had been the first Yom Kippur in our own country. It must surely have been the most significant Yom Kippur ever: a day of profound grief for the many who had fallen, a day of humble thanksgiving for the victory that had been granted us, a day of atoning for the death and sorrow we had inflicted on our opponents.

But in my 21-year-old arrogance, feeling quite sure that I had outgrown religion and tradition, I accepted a lunch invitation from the United Press correspondent and went to the Armon Hotel – the only restaurant open in Tel Aviv for the many foreign correspondents in the country. I was the only Jewish person there and I have never felt more ashamed in my life. It was the first – and the last - Yom Kippur on which I did not fast.

When the last battle, Operation Hiram, had been fought and won and the Upper Galilee had been liberated, the P.I.O. became a much quieter place. Suddenly there was time to swim, sunbathe and ponder what to do next.... and that just had to be learning Hebrew. There were no ulpanim yet in those early days, and I felt that the best way to learn the language was to take a year off and live on a kibbutz. It turned out to be a most interesting year but it would take far too long to talk about it here. I emerged from it with fairly good street-Hebrew, but am to this day still illiterate when it comes to writing.

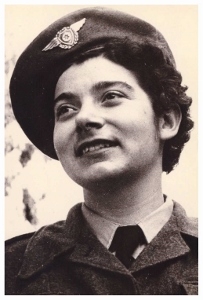

Once my year was up I was expected to come back and work in the Foreign Office but I felt very strongly that, in order to become a real Israeli, I would have to do my army service like everyone else. I was, of course, by then four years older than the average recruit of eighteen, but they accepted me and I was allocated to the Air Force base in Ramle.

Suddenly, everything was strange, chaotic, loud, tough, depersonalized and totally unfamiliar. I had become a number without identity and I can still sense the smell of the Quartermaster's Store in which we had to line up to be given our uniforms, boots, berets, blankets and mess tins. We slept in Nissen huts, ten on each side; reveille was at six, lights out at ten.

It was 1950 by then and the vast waves of immigration were well underway. Operation Magic Carpet had brought the Jews out of Yemen; Operations Ezra and Nehemiah had followed with well over a hundred thousand new immigrants from Iraq and Morocco. This in addition to the remaining survivors of the Holocaust who were still coming from the D.P. camps in Europe. And everyone over the age of eighteen, except for the ultra-Orthodox, was expected to go into the Army.

The Army was the great equalizer and we all had to go through the same mill. We were medically examined, injected, sprayed with D.D.T. and examined for head-lice. The basic training was hard and I can't say that I ever became a particularly good shot. Among the things I hated most was the total lack of privacy. Everything, but everything, was done in groups and I remember the joy I felt when, one day, I discovered a shower cubicle for one person only, unlike the large shower room which we all used every day. I luxuriated in my "private shower" after that, until two days later an officer marched in followed by three girls, their heads wrapped in bandages, and yelled at me, "What on earth are you doing here?" It appeared that I had unknowingly been enjoying the delousing shower – and I was very sorry to leave it!

By the end of three weeks we had been knocked into some sort of shape and there was even a new camaraderie emerging. Despite our different languages, backgrounds, cultures and ages we were beginning to be soldiers. Once basic training was over, everything changed completely, and from being just another cypher, I was now allocated to the Intelligence Service and given the job of Public Relations Officer though, alas, with the rank of a very new Private.

Although the war was over, Israel had sadly never been free from skirmishes and attacks from Fedayeen infiltrators. The foreign press and visiting politicians or V.I.P.s were therefore never far away and unceasingly interested in the few old Spitfires and Piper Cubs which more or less constituted the Israeli Air Force at that time. All our pilots and most of the technical personnel had either come with the Machal or they were Israelis like Ezer Weizmann who had served with the R.A.F. during the war. So it was useful to have someone like me, who was not involved in operational tasks and whose English was good enough to draft press releases and write a regular newsletter (which was, incidentally, later translated into Hebrew for general circulation).

I remember one particular press conference at which there was a Colonel, a Lt. Colonel – and a Private- Aliza Blum – which was me. I felt a total fool and it became obvious that, if I wanted to keep my job, I would have to go through the officers' training course.

Bad news indeed and I quietly hoped that I might not pass the many psychometric and other tests to assess my suitability. But no such luck, and only four months after finishing my first encounter with square bashing, I was sent off to Sarafand (Tzrifin, as it is called in Hebrew) to learn what real military training was about.

Looking back, the next three months were certainly physically the hardest I have ever experienced. But I was also really proud that I managed to stay the course. Climbing ten-foot walls, with full kit, rifle and bayonet included, was not my natural pastime, nor were five-day manoeuvers in the glaring heat of the Negev, bayonet training or night orientation exercises with nothing to guide me except the stars.

A whole new world opened which culminated every second Friday at noon when we were due for our fortnightly weekend leave and stood rigidly to attention for barrack inspection. Our Sergeant Major was ex-British Army, and we were sure that his voice was loud enough to be heard in Tel Aviv. He would come round, wearing white gloves and dress uniform, and would pass his white-clad index finger over each available inch. If the slightest speck of dust adhered to his glove, our leave was cancelled! It was good training. I learned invaluable discipline as well as how to adapt and fit in, and I was certainly never again as fit as I was at the end of the course when, at the passing out parade, we filed past the High Command proudly displaying our hard-won gold bars on our epaulets.

Those first years in Israel were wonderful years because for each one of us life had a purpose, a meaning that was infinitely greater than the self. Unlike today, when Israel has become prosperous, materialistic and self-seeking from the leadership down, those early years were hard, materially; we all had little and lived very modestly. Food was rationed but the "spirit" was not. They were years of togetherness when a common goal fired us all. At least we were free, we were independent, our children would grow up not having to look over their shoulders, no-one would call them 'dirty Jews' and never again would we need to be passive victims.

Comments