Righteous Japanese who saved Thousands

The little agricultural town of Yaotsu sits amidst the picturesque countryside of central Japan. Its claim to fame is as the birthplace of Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese diplomat who saved the lives of thousands of Jews in Lithuania during World War Two.

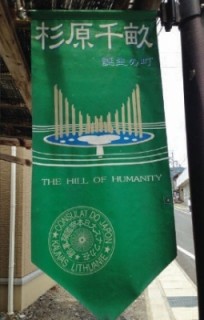

In 1990 Yaotsu declared itself a Peace City, in 1994 it created the Hill of Humanity park to commemorate Sugihara, and since the year 2000, the town has operated a memorial museum.

Twenty thousand people visit the Sugihara Memorial Hall every year, the great majority of them Japanese. In fact, a major aim of the institution is to educate the Japanese not only about their heroic countryman, but also about the history of anti-Semitism and Nazism.

Detailed commentary on all exhibits is presented in English, Japanese and Hebrew. And among its 20,000 annual visitors the Sugihara Memorial Hall counts 2,000 Israelis.

Descended from a Samurai family, Chiune Sugihara was 39 in 1939 when he was appointed vice-consul in Kaunas, Lithuania (formerly known as Kovno), the second largest city in the country, where he was stationed with his wife and young sons.

Polish Jewish refugees began arriving in droves to Kaunas after fleeing across the border from Poland, which had been conquered and occupied by Nazi Germany.

By spring of 1940, 15,000 were congregating there. In June 1940 the Russians invaded and annexed Lithuania. They ordered all the embassies closed and all diplomats to vacate.

The refugees began in panic to look for an escape route. Through the efforts of Honorary Dutch Consul, Jan Zwartendijk, there was a possibility to enter the Dutch colony of Curacao in the West Indies, although this "entry visa" was in reality a fictitious sham in order to create the illusion of a final destination.

But in order to travel to Curacao the only open route was eastwards through the U.S.S.R. and then through Japan. The catch was that Russia would not admit anybody unless he could show a valid Japanese transit visa. This visa would allow the holder admittance into Japan and to stay there for a limited time.

In July 1940 a Jewish delegation met with Sugihara, described the plight of the refugees and begged him to issue visas. Sugihara cabled three times to his home office in Tokyo requesting permission to issue transit visas. Three times permission was denied unless the refugees met strict criteria, which they did not.

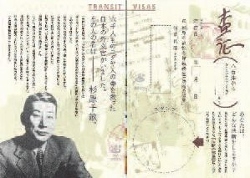

Sugihara took his fateful step: he disobeyed orders. Over the following two months he issued more than 2,000 handwritten visas, allowing the refugees to enter Japan on a transit basis.

He also negotiated with the Russian authorities to let the Jews travel by train through Russia on the Trans-Siberian Express. Aided by his wife, he is reported to have written up to 300 visas per day, and continued to write at a feverish pace until the end of August 1940.

Lines of refugees snaked outside the Japanese consulate, even waiting overnight. By this time all diplomatic offices had been shuttered except those of the Dutch and the Japanese. He postponed his departure until the last minute and kept writing visas until the last minute, until the first days of September 1940 when his train left Kaunas.

Sugihara was among the last diplomats to vacate the city. It is reported that he continued to write blank visas and throw them to the crowd even as the train was about to depart, and also that he deliberately left his seal behind so more visas could be written in his name.

There was no suggestion that he acted for personal gain. He had no personal ties to Jews and no background which could explain his conduct. He simply opted to do good up to and beyond what could be predicted or expected.

Since many visas covered whole families, it is estimated that between 6,000 and 10,000 people were directly saved by Sugihara visas.

After arriving by train in Vladivostok, many went to Kobe, Japan, where they stayed for several months before traveling onwards to destinations around the globe. Others went by train from Vladivostok to Korea and then by ship to Shanghai where they lived out the war.

After Japan occupied French Indochina in July 1941, passenger sea travel was discontinued, and the Jews remaining in Kobe were transferred to detainment in Shanghai. Although it was an ally of Nazi Germany in the war, Japan did not cooperate with the Third Reich's anti-Semitic policies. It neither killed a single Jew nor handed any over to German authorities.

Today descendants of Sugihara refugees number in the many thousands and live scattered over the globe.

Sugihara continued his service in the Japanese foreign service in Europe during the remainder of the war.

In 1944 he was arrested by the advancing Russians and interned with his family in a POW camp until 1946. Upon his return to Japan in 1947 he was retired from the Foreign Ministry.

It is under dispute whether he was being punished for his insubordination or whether his dismissal was due to downsizing after Japan's defeat.

Sugihara was never reprimanded or charged with misconduct, but he had to start life anew. He and his family lived in very modest circumstances, bordering on poverty.

In 1968 Sugihara was located by Jehoshua Nishri, one of his former refugees who was then serving as attaché in the Israeli embassy in Tokyo.

Sugihara was invited to and visited Israel; his eldest son studied at the Hebrew University. It took until 1984 for Israel to bestow upon him the honor of Righteous Among The Nations. When this recognition brought Sugihara to the knowledge of his former refugees, some raised substantial sums of money to try to help him.

But by then Sugihara was old and frail. Chiune Sugihara died in 1986. His wife wrote a memoir, Visas for Life, and she and his sons continued to promote his legacy. As part of his state visit to the United States in April 2015, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe toured the Holocaust Museum in Washington.

In front of a memorial honoring Sugihara, Abe stated: "As a Japanese citizen, I feel extremely proud of Mr. Sugihara's achievement.

"The courageous action by this single man saved thousands of lives."

ESRA's children of the Sugihara refugees

ESRA members Reuben and Nathan Mowszowski are children of Sugihara refugees.

Their parents left Bialystok, Poland, in 1939 for Lithuania where they found themselves stranded by the war.

After standing in line for days outside the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, they were able to secure visas from Sugihara for themselves and members of their extended family.

The family traveled across Russia by train, and then onwards to Kobe, Japan. Thenceforth they went via sea to Mozambique and South Africa. The Mowszowskis' parents and brother eventually entered Palestine in 1941 on forged visas.

Today Reuben Mowszowski maintains a historical archive and collection of Sugihara memorabilia, including commemorative stamps issued by Israel to honor the Japanese consul.

The heroism of the man is conveyed in a museum with a message of peace

The Sugihara museum in Yaotsu tells the story in a dynamic and moving way through documents, photographs and film. Although the artifacts are not originals, a sense of sanctity pervades, and Sugihara's heroism is conveyed.

One Sugihara survivor donated his original passport bearing the Sugihara visa. This passport is kept for safekeeping in the Yaotsu town hall; a facsimile is displayed in the museum.

A life-sized installation recreates Sugihara's office in the Japanese consulate in Kaunas and the desk at which he sat while inscribing the visas.

Every visiting group is greeted by Hanit Livermore, an engaging and knowledgeable Israeli working at the museum. Interacting with the audience, Hanit explains the Sugihara story as a lead into the larger lesson of the Sugihara: the sanctity of altruism.

In the landscaped grounds in the park outside, this universalist message rings loud and clear. Statues and memorials dot the expansive park.

A large statue of chimes surrounding a reflecting pool plays a melody – "Wishing for Peace".

A winding pathway is lined with busts including a dramatic one of Albert Schweitzer.

A large sculpture entitled Bells for Peace overlooks the valley. Its three soaring pyramids constructed from layers of large flat stones rest one atop another.

The flat stones signify the refugees' passports into which Sugihara stamped his visas.

Inscribed on bells at the apex of each pyramid are the three values to which Sugihara said he aspired: love, courage, heart.

Nearby, Chiune Sugihara's statue portrays a handsome face emanating dignity and kindness. "Don't try to be a hero," his gaze seems to say. "Just be human."

Comments