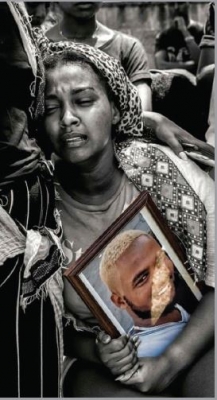

A Father’s Anguish

Out in force on the streets ... one of the protests over the death of Ethiopian Solomon Teka (Photos: Efraim Wase)

Out in force on the streets ... one of the protests over the death of Ethiopian Solomon Teka (Photos: Efraim Wase)

Translated from the Hebrew by Nina Zuck

The protest following the killing of Solomon Teka caught me in a meeting with the top brass of the Israel Police, at the end of which I went away sad and confused. I was held up for hours in a long traffic jam, and eventually collected my family who were waiting for me at my mother-in-law's home. On our walk home I tried to push aside the horror that was likely to develop into a national social crisis. On our way we met many members of the community out on the street to voice their protests.

My six-year-old son had heard in the news about the incident and overheard the conversation among the adults. As he walked he asked me why he sees only brown people like us outside. Did something happen? Why are there no "feranjim" (white people) on the street? I answered that people are outside because they want to live in a fair society in which everyone takes care of each other. But he is a clever child, and understood that there was something deeper going on here; he answered both himself and me, "I know you do not tell me the whole truth because there are only brown-color people here and I know why." I looked at him in amazement and asked, "What do you know?" He bombarded me with questions: "Is it true that they are outside because a policeman killed an Ethiopian child? I thought that policemen are good and stop thieves, like Yaakov (the community policeman) and the police officers at your work (community police)? I saw on TV people who burned things; what could cause people to burn things that are not theirs?"

I answered that they are angry and feel they have no hope and no future. People without hope sometimes do things that are not allowed so that they will be heard and something will change before they finally give up, so that they will be taken seriously. But you, my son, have to understand that you should not do these things ... I tried to explain to him: "When you were four, I promised that I would buy you a bike if you would be a good boy who helps at home. You really tried your best, but I was unable to buy you a bike at the time and told you that you had to be patient and wait. You cried because you were angry that I could not keep my promise? One day you were so upset that you turned the whole house upside down. When I asked why you made such a mess you said it was because I did not keep my promise. That's what happened to those people. You destroyed things not because you hate me, but because you had no more patience and you wanted me to take you seriously. So the people you saw on television did not make fires because they hate; they did not burn because they are bad; they burned because they are asking to be accepted, to be allowed to reach their aspirations, not to be hurt or humiliated; they want to feel safe.

He continued to ask, "When Eliya and I are big children, will white people hurt us? Are Israelis just white people? Is the Land of Israel only for white people? Am I an Ethiopian? How do we become white? Why were you born in Ethiopia and not in Israel?"

I don't know how to answer these questions. From their earliest days, I taught my children that the world is beautiful with lots of colors, otherwise it will be a gloomy, gloomy world; I taught them that people also come in different colors and they can be brothers. I told them that all of us are Jews who were scattered in all kinds of countries. Now that we are here in Israel, we are One Nation; we are a special and united people who care about each other, and are an example for the rest of the world. As I gathered myself for each question and looked for explanations, suddenly my head bent down and I began to cry. My son asked me why I was crying. I cried because I am very sad. I paused for a moment, looked deep into the pure eyes of the child, hugging him and his little brother as hard as I could so that they would feel secure and calm. I told them that I would protect them from any threat for as long as I am alive.

Do you know the strong need parents have to protect their child at all costs against any threat and sense of uncertainty? My feeling as a father is deep fear: I know that my son's sense of security is in my hands; his innocence has been broken. He will be forced to find his place in the world and be strong, to build his character and find inner peace. I understand that he feels imminent danger, a danger that troubles his inner world.

I ask my Israeli friends: Have you ever had this kind of conversation about being alien with your children? When my sons reach the age of ten, am I supposed to fear for their fate in a random meeting with the law enforcement authorities? And in later stages, when they want to build their future, will the roads be blocked in front of them, will they and their generation be forced to fight for legitimate things like security and belonging?

Our struggle as a unique and ancient community for generations does not begin today. It began back in time, in the Diaspora, in the mountains of darkness when our forefathers established an ancient kingdom and were a proud community in the face of hostile Christian empires. They established Jewish kingdoms and even sacrificed their lives for the observance of their religion. In Ethiopia, our skin color, which is identical to the local population, enabled us to assimilate into the Christian Ethiopian state and its population, but our forefathers and parents chose to emphasize our difference by adhering strictly to our Jewish faith, which was an expression of isolation and pride. We will return home to Jerusalem - so they prayed over 2000 years.

When the young state of Israel arose, our forefathers felt the time of the Messiah, the time of redemption had come, and so they tried with all their might to reach their goal of building the country, and building it together with our brothers from the rest of the Diaspora. Being different and foreign was a strong deterrent to the old establishment, and so our arrival was delayed. And in the 1980s, when we finally succeeded against all odds to cross the soil of Sudan, because of our burning belief and boldness that cross the boundaries of imagination, and to realize an ancient dream, our story was pushed aside. By the time we arrived in Israel, our parents, who had preserved thousands of years of their religion and faith in the knowledge that they were the last remnant of Judaism, were required to undergo conversion to Judaism and experienced contempt for their Judaism. Many of them had no choice but to accept the decree and were silent because they believed that for Jerusalem it was necessary to remain silent. When they changed the names of their children – names which had been chosen carefully and with meaning, they were silent and lowered their heads. When they were required to send their children away to boarding schools as if they were not proper parents and educators, they were silent and lowered their heads because they believed that their children would become Israeli in every way. They believed that their integration into the new society would be quick and optimal, that they would be proud Israelis belonging to society and to the state without feelings of inferiority and fear. When they were told that the spiritual leaders who had guided and guarded them as a community for thousands of years were unworthy and therefore had no authority, our parents tried to fight as hard as they could.

However, the culture shock, their exhaustion from the hardships of the journey, their confusion and pain from the sacrifice required when burying their loved ones on the dirt roads of Ethiopia and the deserts of Sudan, and their weakness vis-à-vis a mighty institution of power and patronizing society kept them silent in the knowledge that tomorrow would be better and a worthy future, if not for them but for their children. And the same song has been sung for thirty years and more. Despite this, and despite the many difficulties and challenges in Israel, our parents never gave up on their wisdom, and in their unique ways they acted to influence and shape our future. In a language they do not know, they can produce just protests and cry out what is in their hearts, united in one firm and confident voice, but with love for the state and the society, because we have no other country. They conducted struggles and reached a dialogue not through weakness, but with the knowledge and understanding that the great danger to the state and its survival would be an internal division between brothers after being united after thousands of years.

For us this is a struggle for our future and our children. In struggles of this kind people will work with all their power to bring about change. There is a feeling that we have tried every way and there is no significant change. Therefore, the protest is beyond the story of the killing of Solomon Teka by a policeman who is supposed to protect the citizen, a policeman who is supposed be there for everyone, and who in turn represents the government and the state in its attitude toward Beta Israel. The killing was the catalyst.

In order to understand the intensity of the protest and the way in which it developed, we must look deeper and deeper into the daily reality that the Ethiopian community experiences: a mother and child in school versus a racist educator; a person who works to make a decent living and experiences daily humiliation from a heartless manager; the fear of losing a job if the employer does not like the color of our skin regardless of our ability; the feeling that we are always expected to be thankful; the feeling when you see your white friends running to donate blood and you look for an excuse to avoid walking with them because you are ashamed that your blood is inferior and therefore would be thrown away; the knowledge of secret birth control injections being given to women without informing them – that you are being "diluted"; the feeling when you're driving in the car and a patrol car passes by and the police look at you and you look away from them trying to behave normally, afraid you'll be asked to stop and you worry if it will end in peace; the feeling of exclusion from clubs and recreation centers because you are black; the contemptuous and condescending attitude on the street, and the feeling that we will never be worthy enough.

All these are the reality of members of the community as a matter of routine. As manager of a community center for Ethiopians, I encounter every year too many events in the summer camps where the children of the community come to me crying because their white friends called them Negroes, monkeys who came from the jungle. I find myself with the staff trying to instil values of respect for others and loving your neighbor as yourself. And I ask the question: where does a child learn how to speak like this if racism and hate are not deeply rooted in his home? A former board member of the organization in which I worked was interviewed several years ago on the regional radio. He complained: why should we give support to summer camps for Ethiopian children who do not have enough means? And he cried out shamelessly that he does not agree - instead of talking about mutual responsibility. Not every family is able to give their children a summer camp to be enjoyed like all the other children in Israel, regardless of origin or who has the means to pay and who has difficulty. He should be thanking God for his good luck. And now, following the protest, I am not surprised at the amount of venom and hatred he is spreading on the social networks. I can continue with many examples that will reflect our daily reality, which is not known to the general public.

The story of the protest is beyond the killing of Solomon Teka and the other young men who have died. This is a story about the desire of the human spirit that has accumulated overt and covert oppression for over thirty years, and this spirit is raising its head today, kicking full force and demanding to live in dignity, safety and security. It's demanding its rightful place in society and no power in the world can stop it any more, no matter what price it will have to pay. The young generation refuses to be submissive and bow its head, and asks an old proud tribe to raise its head and be upright, a generation that refuses to be content with scraps of crumbs. It is a generation that feels imprisoned and suffocated without hope and now seeks to find its legitimate place as every person wishes for his children This is a generation that is prepared to wage a struggle and feels that it has nothing to lose but as a society and as a people Am Israel will definitely lose. Is that what we want? Is there only division and polarization?

This angry child cries out for rescue before it is too late. He asks for a lifeline, a guiding hand and a big hug that will tell him "you are protected" because only then will he grow mature

with strength.

Many ask me what is the solution? I find this too enormous a question for me, but there are basic things in the conduct of the person for whom you do not have to be a great scientist or a great educator to understand. Basic things that any human being can identify with without having to fight for. Racism has today received official approval through building a consciousness that turns "us" into "them". The delegitimization that the media and the establishment created toward the Ethiopian community only continues the trend of disintegration of the Jewish people as one nation into a tribal society that hates each other.

For forty years we have been working hard and trying to integrate ourselves under the humiliating looks and in accepting every decision that has been made for us. Lately we have brought our stories into the salons of your homes and workplaces. Young and old alike told their stories to try and reduce the alienation and ignorance of who we are and how we came to be here. We have come into the schools and kindergartens as parents to expose our heritage and culture to your children who have often humiliated our children about the color of their skin, We held a dialogue with police officers in order to reduce possible charged encounters.

In order to create real change, a deep and courageous inner soul-searching is required in which everyone will ask himself what has he really done and how has he really acted? Do I see black people and their culture as human beings equal to me? If I do, I will not let my children humiliate a different-colored child in kindergarten or school - because in the future they will become adult racists. We need deep and meaningful basic education of Israeli society before we are lost completely. If we harm the elderly or the weak, if we kill a person who crosses us in a parking lot or on the road, if we accept kindergarten teachers who harm young children, we are losing our human way. If we accept that our children document and pride themselves on group sex abroad, there will be no turning back. The feeling is that "in these days there is no king in Israel, and no one to see who is doing the right thing." As if we have returned to the days of the Bible where the earth is silent for twenty, forty years, a shabby and spoiled society that values only itself, and in the absence of a king in Israel, civil strife and arguments begin to emerge, and therefore the danger to our existence will harm our strength as a people and a state.

A people needs a moral and ethical compass from the person who heads it and leads it. Therefore, in order to create a fundamental and conscious change, a leadership is required that places its main emphasis on social cohesion and moral compass. A leadership in which the central value is "Love your neighbor as yourself"; a society in which we are one whole nation. Otherwise, we will become a morally and ethically rotten society as a nation and a people, and no nation can survive in a tribal state. It will be the beginning of the end.

Comments