Yiddish Speaker – Teach Yourself English

Some time ago, an interesting book came into my possession: English Home Teacher: Practical Lessons in English by Alexander Harkavy. It reached me via a circuitous route and with an interesting history. My wife Yona's family, all Holocaust survivors: her father Meir and mother Tsila, together with her mother's mother and a brother, had come to Israel in 1949. The eldest sister remained in Russia. Meir's entire nuclear family had perished. A few years later, Yona's uncle and grandmother left for the United States to join her other uncle, also a Holocaust survivor, living there. In 1956, her aunt (the eldest sister) succeeded in leaving the Soviet Union. After spending some years in the States, staying with her brothers, and helping to look after their young children, she finally settled in Israel. She brought with her the book English Home Teacher.

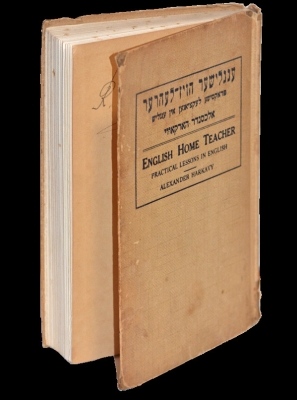

Aunt Gesia was fluent in Yiddish, Polish and Russian; but the pressing need was to learn English. Caring for her nephews and nieces left little time for formal study. It was then that she acquired the English Home Teacher: Practical Lessons in English. A New Method for Home Instruction which had been expressly written for Yiddish speakers to learn English.

The book's author Alexander Harkavy was a most noteworthy gentleman, both talented and industrious. Born in 1863 in Novogrodek, Belorussia, the grandson of the town rabbi, Harkavy showed an early interest in languages, acquiring knowledge of Hebrew, Russian, Syriac, German and Yiddish. Moving to Vilna at the age of fifteen, he wrote his first work in Yiddish and three years later, after the pogroms of 1881, immigrated to the United States.

Harkavy's love of Yiddish together with his gift for languages soon crystallized into a vocation. Before making New York his permanent home in 1890, Harkavy had led a peripatetic life, alternating between Europe and North America. He helped found a Yiddish newspaper and also a periodical. Once settled in the Big Apple, his literary output was prodigious. With many Jews from Eastern Europe arriving and not having the time or opportunity to formally learn the new language, Harkavy published Der Englishe Learer (The English Teacher) in1891 and Der Englisher Brivnshteler (The English Letter Writer) in 1892. He wrote in the immensely popular, "English self-taught" genre expressly geared for Yiddish speakers.

After four decades in the USA, Harkavy was well versed in the contemporary culture. He was fluent and well-read in the vernacular. Living in New York, he was thoroughly conversant with the current trends of American society. He was also on intimate terms with the immigrant experience of his co-religionists. He knew full well the basic English required in order to survive and make a living in this new and daunting land.

Harkavy's talents were not confined to textbooks. In his prolific career, he translated Don Quixote into Yiddish, revised the King James English Bible, translated it into Yiddish for a dual language version and, also compiled and contributed to many Yiddish anthologies and publications. Among his many other activities, he taught American history and politics for the New York Board of Education as well as Yiddish literature and grammar at the Teacher's Seminary in New York. Harkavy's lasting contributions, however, were in lexicography where he compiled Yiddish-English and English-Yiddish dictionaries. His crowning achievement was the Yiddish-English-Hebrew Dictionary (1925) which played an important role in educating East European Jewish immigrants. It is still in use today.

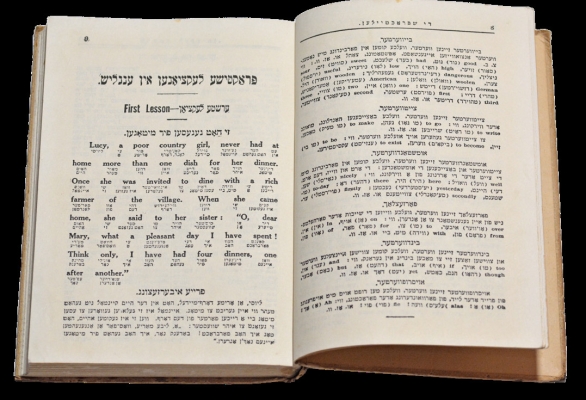

The English Home Teacher: Practical Lessons in English, first published in 1921 and reprinted in 1929, is both a fascinating and enigmatic book. The 272 pages contain 50 lessons, each of which commences with a short passage in English, each word accompanied by its translation and a pronunciation guide. It is then followed by a grammatical exposition that often has no direct connection to the passage itself. Naturally, all the explanations and pronunciations are in Yiddish in Hebrew script.

Didactically, to put it mildly, the book is no great shakes. In fact, it would make the eyebrows of a modern and trained English teacher curl. It has no logical, graded structure or progression, no revision or reinforcement. In the very first lesson, the neophyte English learner is served a heady brew of past simple active and passive verbs, present perfect tenses, plus a comparison of adjectives. Moreover, as the pronunciation guide for each English word in the text is written in Yiddish, to hear someone's first attempts at enunciation would have been interesting. Nevertheless, bear in mind, that this book was written over a century ago; when the science of teaching language had barely emerged from its swaddling clothes.

Logic would dictate that the English be modern, the passages be relevant, and the vocabulary be both practical and utilitarian. This would enable users to interact and communicate with their surroundings. Reading the contents of the introductory reading passage in each lesson, therefore, is puzzling because the writer has chosen to take the opposite tack. Most of the passages are anecdotal, often piquant, and pithy with a moral attached, while others are homiletic. Their contents, furthermore, are mainly drawn from early Victorian England with the corresponding vocabulary. A great stretch of the imagination is needed to see how archaic terms such as: "a droll fellow, to dine, a duke, an incision, the latter, a witty idler, a tankard, a draught, taken counsel, took lodging, a roguish companion, whereupon" etc. could be put to daily use or even understood in the Bronx.

What were Harkavy's motives in choosing the texts? Was he trying to show off and impress his readers with his erudition and grasp of English? This does not seem likely as he was well known and highly regarded in the community. His learned reputation went before him.

Harkavy, having grown up in the world of Talmud studies, was familiar with the tradition of exegesis, wit, pilpulim (hair splitting argumentation and debating) and knew that many new immigrants from Eastern Europe had a similar background. Possibly, he chose the reading passages in order to appeal to their tastes for most of them are witty, humorous, and thought provoking. The introductory passage to the third lesson begins: A lunatic in an insane asylum was asked how he came there, and he answered: "The world said I was mad, I said the world was mad and they outvoted me." Much food for thought.

The English Home Teacher: Practical Lessons in English was first published in 1921, a year that boded ill for the millions of Jews wishing to flee the persecution, pogroms, and mass murders of Eastern Europe and of the Baltic states to seek a haven on safe shores. American public opinion and sympathy for all those displaced and stateless had shifted to a fear of being swamped by a wave of impoverished, feeble immigrants; who would cause the growth of slums, expose workers to cut throat wage competition and endanger American living standards. With the passing of the Emergency Quota Act that same year, the United States had declared a moratorium on its immigration policies and had begun to drastically restrict the number of newcomers. Australia, Canada, South Africa and other countries had followed suit.

With his finger on the pulse, Harkavy was, undoubtly, painfully aware that the Jewish newcomers from Eastern Europe fitted the popular and biased stereotype of the unskilled and indigent immigrant with broken or non-existent English. Maybe he felt that his book offering reading passages on a 'high level' would enable its students to acquire a more sophisticated vocabulary with better communication skills; thus dispelling this negative image, ease integration and aid entry into the work market.

Anu Museum of the Jewish People, situated on the campus of Tel Aviv University, has in its archives a film of Harkavy's visit to Novogrodek in the early 1930's. The atmosphere was festive – for here was a native son who, had made good in the Goldene Medina, returning as a celebrity to pay his respects to his birthplace. The feted guest was escorted around town and proudly shown the Jewish institutions: the mikveh (ritual bath), the synagogue, the yeshiva and the Talmud Torah with the little children studying diligently at their tables.

The film, however, is bittersweet and sad. It serves as yet another testimony to a Jewish presence wiped out during the Holocaust. In 1941, the German army occupied the town. The 10,000 Jewish inhabitants, men, women and children, comprising half of Novogrodek's population, were ultimately murdered with the assistance of local collaborators. Harkavy was spared the agony of hearing this terrible news. He had passed away in New York in 1939.

Comments