Trio who provided a Baby Sanctuary

A dented thimble, a button, small piece of ribbon, torn piece of material, a hazelnut, ring, coin, small lock and a necklace made up of tiny blue beads, are among a few dozen of what appear to be totally insignificant items in a narrow showcase of a London museum.

However, the story behind the items is anything but insignificant as each and every one were left with newborn babes being handed in at a home for foundlings established in 1739. Many of the mothers were illiterate, and the objects were left as a form of identification should they or a member of their family want to reclaim the infant in the future.

The glass-fronted case containing a few dozen of these small tokens, signaling the gut-wrenching despair, emotional and physical pain of a mother parting from her newborn, had me transfixed, rooted to the floor of The Foundling Museum, the U.K.'s first children's charity. It is situated in Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, the charity known as the Foundling Hospital having been established by sea captain and philanthropist, Thomas Coram together with his friends, artist William Hogarth and composer George Frederic Handel.

The three gentlemen combined their creative and humanistic traits and skills with a joint vision of providing sanctuary to abandoned babies and children at risk. At the same time, they also opened the first public art gallery, becoming a beacon unto others as they emphasized how the arts could support philanthropy whilst also giving a platform for the artist's works to be seen.

Born in Halle, Germany but eventually settling in London, Handel supported the Foundling Hospital through a series of fundraising concerts, and in 1749 a special concert raised funds for the Foundling Chapel for which he composed what became known as The Foundling Hospital Anthem. Such a success was the event that the following year Handel's oratorio, Messiah was performed, becoming an annual Foundling event raising large amounts of much needed financial support for the institution.

Charles Dickens also lived in Bloomsbury and rented a pew at the Foundling Chapel. It was whilst living at 48 Doughty Street that Dickens penned most of his 14 novels, including Oliver Twist. The abject poverty found on the streets of London was brought home through his portrayal of street urchins groomed in the art of pickpocketing by the infamous Fagin, referred to in the novel as "the Jew", and whose creation brought charges of anti-Semitism against Dickens - as did elements of two other rather sinister characters, Ebenezer Scrooge (A Christmas Carol) and Uriah Heep (David Copperfield), the charges strongly denied by Dickens and in subsequent years, by his ardent aficionados.

Dickens' London home is also a museum, within walking distance of the Foundling Museum, but worlds apart – literally - from what would have been daily scenes in the Dickens household and the Foundling Hospital in the 1800s.

The Foundling Museum focuses on the history of Thomas Coram and the years he and his supporters struggled to create a safe haven for impoverished children. And having succeeded, the museum shares with the visitors aspects of the care, education and preparation for life once outside the protective walls for those children brought into the world during this poverty-stricken period and for a few generations after.

These days the period paintings hanging in the hallways, stairwells and gigantic rooms of one of the wings would sit very nicely in any famous art gallery and they certainly do ram home the point that the seafarer, painter and musician jointly envisioned - combining art and philanthropy. Now too, 275 years down the line, the support and contribution of art to charities large and small is more than the norm.

Accompanied by their mother, three children - twin sisters and their younger brother - all clutching pencils and museum-provided worksheets, stood in front of the glass case with the tokens as I approached. Gazing up at the top rows of the seemingly insignificant items arranged above their heads, the children fired questions at their mum who did her level best to explain, in a way that wasn't too harsh on their young ears, that these were items from and signs of the times when so many people lived in terrible poverty, gave up their babies for love of and concern for the child and not because they did not want them.

"Look," she said, pointing to a specific token in the showcase, "this mother left a ring, probably the only one she had, something that was very dear to her, and she pinned it to the clothing of the baby so as to identify her child."

"Mum, what would you have left if you had not been able to take care of me when I was born?" asked one of the girls. Already not quite dry-eyed, the mother protectively reached out to cuddle all three children as she gently moved them along, her answer to the little lady lost to my ears as she lowered her head toward the children.

The history of the Foundling's tokens, and the opportunity to look at a small selection of the 18,000 tokens handed in until 1790, is compelling reading, as each mother was asked to 'affix on each child some particular writing or other distinguishing mark or token, so that the children may be known thereafter if necessary.'

Receipts were introduced in the 1760s, but even then, babies, who were renamed on admission, continued to be left with a token or talisman – and apart from actual objects, written notes and poems were also handed in along with the squirming tiny bundle of new life they had no hope of sustaining.

Curiosity made me enquire as to whether possibly Jewish babies might have been handed over to the Foundling Hospital, and it was also an opportunity to let the staff know what an incredibly moving experience the museum visit had been.

"The museum is certainly a moving place, not only for visitors but for the staff as well," responded Hannah Thomas, the Foundling Museum's Marketing and Communications manager.

"I've had a chat with our Collections team and we can't think of any Jewish connections in the history of the Foundling Hospital, as it was very much an English institution. There may well have been Jewish children but they would have been baptized as Anglican on arrival and we wouldn't be able to identify them."

The museum showcases the physical conditions in which the children lived, learned, were nursed through illnesses and diseases rampant in those days and were expected to join the work force when still very young. In an alcove, large black and white photographs of the dormitories hang on the walls around a metal framed bedstead with a thin mattress, recordings of some of the latter year 'graduates' telling of the strictness of the staff, the emphasis on cleanliness, obedience, going to chapel and more. As much as those working at the institution might have, or not, tried to give the children some level of affection, they understood that they had been rejected, handed over to others and many cried themselves to sleep at night.

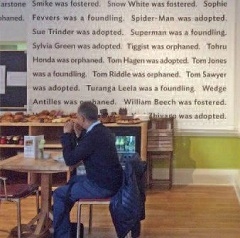

On the ground floor of the museum is a large, very bright and hugely inviting café, especially welcoming after entering, and much relieved to leave the stark world of Victorian and later periods of poverty and suffering. It is not only the smell of the coffee, tea and cakes that is so inviting but the surrounding walls, covered from top to bottom with the names of fictional characters who had been orphans or foundlings or who had been adopted. Absolutely fascinating reading material, and food for thought as one sips tea and realizes that so many characters had been brought to life and live on so vividly, in some cases centuries after the demise of those who had created them.

One wonders if the children at the Foundling Hospital were read to, or read themselves, stories about those who had started their lives in the most negative of circumstances but went on to have successful or adventurous lives - and if so, maybe helped them shed a few less tears as they lay on their metal framed beds at night.

The Thomas Coram Foundation for Children still exists but is known today just as Coram. In the almost 300 years since its inception, over 25,000 children's lives have been saved, and in modern times, Coram, centered in a relatively new building alongside the Foundling Museum, continues to develop innovative approaches to childcare, education and developments in child psychiatry, and to contribute to the general emotional wellbeing of children.

Overlooking Brunswick Square Gardens, the building next to the Foundling Museum is the University College London, School of Pharmacy, which is undergoing a facelift and is covered in scaffolding. A blue plaque on the wall between the metal poles caught my eye. It read that the Bloomsbury Group, literary folks the likes of Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes and a host of others, lived or met in the early 1900s at a house that was originally on this site and on the other side of the square. Yet another blue plaque notes that James Matthew Barrie, the creator of Peter Pan, had also been a resident of Brunswick Square in the 1880s.

Large illustrated signs placed strategically around Brunswick Square Gardens make fascinating reading as one shares in the history of the buildings and those who lived in them centuries ago. One of the signs deals with the flowers, fauna and birdlife abundant in the small but welcoming park, but I seemed to be the only one actually reading them.

Passing by the park's benches, it seemed to me that the predominent language being spoken by those resting in the park was Polish, and in a large open air area enclosed by a high mesh fence alongside the park, scores of young men were playing soccer on three synthetic grass pitches.

There seemed to be any number of languages being fielded there as well, but the English we heard was not quite repeatable. It was more in keeping with that used by Dickens' Bill Sykes in Oliver Twist..

Comments