Primo Levi - A Great Italian Jewish Author

Report and photographs by Elizabeth Levi Senigaglia

Remembering Primo Levi 1919-1987

April 11, 2017, marks the 30th anniversary of the death of Primo Levi. Some readers will recognize his name immediately; others will question: "Who was Primo Levi?"

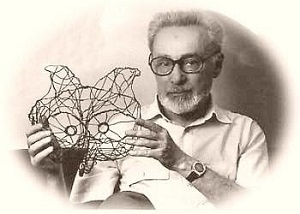

Primo Levi was an Italian Jew, chemist, author, and poet, born in Turin, Italy, in 1919, deported to Auschwitz in February 1944, at age 24, and fell to his death in April 1987 in the stairwell of his ancestral home in Turin, where he had lived his entire life, except for "two years outside the law". Italian police recorded his death as a suicide; his children acknowledged his death as suicide, yet there remains a controversy about his death.

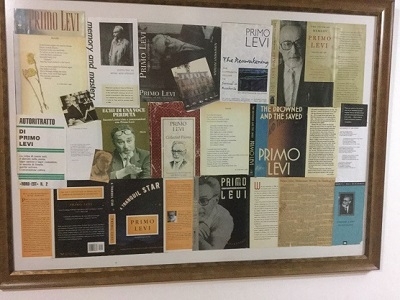

Levi is best known for his autobiographical accounts of the Shoah, among them If This is A Man, The Truce, Moments of Reprieve, The Periodic Table, and the final work of philosophical essays on the Lager, 40 years after his return, The Drowned and the Saved. Through the recently published three-volume set in English "The Complete Works of Primo Levi", a wider audience now has access to his poetry, essays, interviews, and newspaper articles, as well as narrative testimonies and novels.

Levi's works have been recognized in Italy since the mid-1960s, winning several of that country's most prestigious literary prizes. Levi himself is considered one of the preeminent witnesses to the Shoah and the senseless brutality inflicted upon him and millions of others. Simultaneously, he is regarded as a prophet (a term that Levi himself would not agree with) warning of the dangers of powerlessness, cowardice, and forgetfulness.

Unlike Elie Wiesel, whose popularity was almost instantaneous within Jewish circles internationally after the publication of his testimony Night in 1960, Primo Levi remained unknown to most readers outside Italy until the mid-1980s. When Levi visited Israel in 1968, the Israeli public did not recognize his name. It was only eleven years later in 1979, when Levi was already 60 years old, that one of his books, La Tregua (The Truce), recounting his journey home to Turin after liberation by the Soviet Army in January 1945, was translated into Hebrew with a limited press run of 500 copies. At the time of translation, Levi wrote a preface especially for the Hebrew edition, where he stated that he was "happy and proud" that his book was being published in Israel, albeit many years after it had been written.

His first book, Se Questo e un Uomo (If This is a Man), a masterpiece in the genre of Shoah testimony, had not yet been translated into Hebrew. He was not surprised, commenting that the book is a diary of a Lager, a topic that is all too well known in Israel so that it would not be interesting. Nine more years passed before Hazehu Adam, the Hebrew translation of Se Questo e un Uomo, would be published in 1988, forty-one years after the first Italian edition of 1947, and a year after Levi's death.

If This is A Man had no more success with English-speaking readers. First translated and published in 1959 in the United States as Survival in Auschwitz, it was republished in England in 1965 with the correct title If This is a Man.

Levi's second book, the sequel to If This is a Man, La Tregua (The Truce), written in 1962 and published in 1963, received immediate success, receiving the Premio Campiello (Venice literary prize). It is a book filled with the joy of liberation and some lightness and humor, written when Levi was in his early forties, working full time as an industrial chemist and writing poems, essays, newspapers articles, books. He was a father, a husband, and for a short time felt he had "become a man again".

In the mid-1970s he wrote, Il Sistemo Periodico, (The Periodic Table), a collection of autobiographical episodes of his experiences as a Jewish-Italian doctoral student in chemistry under the Fascist regime and afterwards. They include various themes in chronological sequence: his ancestry, study of chemistry, his experiences as an anti-Fascist partisan, arrest, and internment at Fossoli and deportation to the Lager of Buna Monowitz; and his postwar life as an industrial chemist. Every story, twenty-one in total, has the name of a chemical element and is connected to it in some way. The book was published in Italy in 1975 to great acclaim. The English publication in 1984 transformed Primo Levi into a celebrity. He was 65 years old and was invited to the United States on a speaking tour.

Known in Britain and America for a single book, If This is a Man, The Periodic Table was "garlanded with eulogies" from Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Italo Calvino and Umberto Eco. In 2006, the Royal Institute of Great Britain named it the best science book ever.

In 1985, Levi, no longer young, was suffering again from the severe episodes of depression which had haunted him throughout his life and which had been exacerbated by his Lager experience. Primo Levi did not intend to be a writer in 1943; he was a young chemist when he was thrown into a maelstrom.

First, as an anti-Fascist partisan fighting with a small group of untrained friends in the hills of Piedmont, Levi was captured by the Fascist militia in December of 1943. Reasoning that his chances of survival were greater if he denied his anti-Fascist activities, he admitted that he was a Jew. He knew anti-Fascists were shot immediately after the German occupation of northern Italy in September 1943, but had heard only rumors about the fate of the Jews. He learned quickly. He was held for two months in the Italian transit camp of Fossoli, near Modena, from where he, along with 650 Italian Jews, were deported to Auschwitz on February 22, 1944. From Levi's convoy, only 19 returned.

After a journey of five days, Levi was admitted to the Lager of Buna Monowitz, a sub camp of Auschwitz where he was forced to work as a slave laborer for eleven months. He was prisoner 174517, a number he wore proudly until his death and which is chiseled into the granite stone that marks his grave in the cemetery in Turin.

Levi was liberated by the advancing Soviet army in January 1945. When he arrived home to Turin nine months later, following a journey of repatriation that zigzagged through Eastern Europe, he was in trauma, bearded, swollen and in rags.

Levi's writing was a direct and unexpected result of his experiences in the Lager.

During the first weeks at home, as he started to heal, the urgency he felt to give testimony about the unspeakable atrocities he had witnessed and suffered, erupted into writings in prose and poetry, with words evoking the enormity of the tragedy. Within four months, he had completed the first draft of Se Questo e un Uomo and fourteen poems directly about the Lager experience, "Buna", "Reveille", "Sunset at Fossoli", and his signature poem "Shema".

Se Questo e un Uomo and its epigraphic poem "Shema", which echoes Judaism's central prayer, represent the core of what the Lager experience signified for Levi and hint at the moral concerns his later writings would encompass. What hurt Primo Levi most was the demolition of a man; "what man had made of man" at Auschwitz.

Levi paraphrases the last four lines from the prayer which form the backdrop for his curse to future generations should they fail to heed the commandment to remember "what man had made of man" at Auschwitz. It is the invocation of a prophet.

Shema

You who live secure

In your warm houses,

Who return at evening to find

Hot food and friendly faces:

Consider if this is a man

Who labors in the mud

Who knows no peace

Who fights for a crust of bread?

Who dies at a yes or a no.

Consider if this is a woman,

Without hair or name

With no more strength to remember,

Empty eyes and womb cold

As a frog in winter.

Consider that this has been:

I command these words to you.

Engrave them in your hearts

When you are in your house, when you walk on your way,

When you go to bed, when you rise.

Repeat them to your children.

Or may your house crumble,

Disease render you powerless,

Your offspring avert their faces from you.

Now 72 years after the liberation of the camps, hundreds, if not thousands of Shoah survivors have written testimonies; pieced together their stories in diaries, essays, and articles. What is there about Primo Levi that makes his testimony so unique that one scholar wrote in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera upon his death: "We will find his works standing before us even at the moment of the Last Judgment."

American essayist and critic William Deresiewicz has written that Primo Levi is the rare writer about whom it can be said that "his literary virtues originate and are almost inseparable from his moral ones". Levi has an uncanny ability to guide us through the horror of the camps, which stems from his powers of precise observation and vivid recall of visual images during his 11 months as a slave laborer. Levi is determined not to distort the record with self-pity or sentimentality; he has chosen the composed language of the witness rather than the lamenting voice of the victim. He has exchanged any possible desire for revenge for a need to understand the phenomenon that is devoid of any understanding. Primo Levi remains with us long after we have finished reading his work.

A few years ago, while on an outing to Haifa from my home in Tiberias, I wandered into Primo Levi Square, in the neighborhood of Ramat Shaul. I did not know that a square had been dedicated to my beloved writer. Between smiles and tears, I asked people when the ceremony had taken place. Quickly I learned the square was dedicated in 2012 on the 25th anniversary of Levi's death. Primo Levi would again have reason to be "happy and proud". I hope he is finally at home.

Comments