Legacy of Negev's Dr. Doolittle

Dr. Doolittle from the Negev passed away – and fans the world over are mourning.

Prof. Reuven Yagil won international recognition for his research on camel milk, but in Beer Sheva, Israel, he is remembered mainly for his free treatments of the neighborhood dogs. Here's the story of the life and death of the mythological veterinarian.

Professor Reuven Yagil, who passed away recently at the age of 84, was not well known to most in Israel, but in the Negev in general, and in Beer Sheva in particular, his name was legendary. He was a leading veterinarian, considered a world expert and a cutting edge researcher on camel milk. He believed camel milk could solve the problems of hunger in Africa and bring relief to millions of ill people. From the 1980s onwards, he published many articles and research reports which received worldwide recognition. This led to his participation in UN delegations and to his work as a consultant to international organizations in developing countries. Researchers from all over the world came to visit the camel farm he founded in the Arava. His findings are used today in a variety of industries.

"Degrees and recognition did not interest him, only 'tachles' (content)", says his daughter, Illana Karman. "He traveled a great deal overseas, met important and high-ranking people to teach them about his research, but he always remained humble and modest. In addition, he would always talk to them about his two great loves – food and football. He did not become rich from his research. For additional income he opened a private clinic for pets, but half the people did not pay him because he always found a reason not to ask for money. From one person he did not feel comfortable asking for payment, another was just a child, the third had come from a long distance, and so on."

His daughter and other family members were pleased to learn that a few days after his passing, his first name, Reuven, was given to a camel born on a farm in Minnesota, USA. The family has been receiving many condolence messages from camel enthusiasts all over the world, who benefited from his immense knowledge. They all describe Prof. Yagil as a charismatic, warm man who loved to laugh, teach, and research. Some of them emphasize the fact that he was an entrepreneur ahead of his time, in that he developed instruments and techniques for in vitro fertilization in camels, and for making ice cream from camel milk, which he named humorously Camelida (ice cream in Hebrew is glida).

Many remember him as the Israeli veterinarian who found a link between the use of camel milk for treating juvenile diabetes, autoimmune diseases, ulcers, anemia, and even autism. To this day this milk is used in many countries to treat stomach problems, infections and allergies.

"Yagil saved many lives all over the world", says Randi Winter, a social entrepreneur from Canada. "A book he wrote at the request of the UN has become the bible for camel farmers. He gave presentations at conferences in Oman, India, and Ethiopia, among other places. He taught a nomadic tribe in India how to raise and milk camels, as well as chefs for a Persian Gulf princess how to make Camelida. He crossed physical and mental borders to help people, and broke many barriers between Jews and Arabs."

In the small Beer Sheva neighborhood where I grew up, Prof. Yagil was a source of pride. Our very own Dr. Doolittle, who arrived from South Africa with an Anglo-Saxon accent and an international reputation. He never refused the neighborhood children who would knock on his door with their pets or just stray animals they found – dogs, cats, frogs, hamsters, and birds. He would treat them all (yes, for free), and many times he would operate on them in front of our astonished eyes.

His wife, Bracha, grew used to seeing strange things in her home. "One day a boy came with a sick snake," she recalled. "I told him to wait by the door until I climbed on a chair, and only then to come in. Another time a plastic surgeon colleague arrived in his lab with a human finger that had been severed in an accident, to ask his help in re-attaching it. After a few minutes the surgeon rushed back to the hospital to continue the operation. After he left, Reuven made himself a cup of coffee and ate some homemade cookies when a neighboring lab assistant came in. He offered her a cookie and after she left, he noticed the finger lying on the table. Planning to return it to the hospital, he finished the cookies and put the finger in the empty cookie bag. A few moments later, the neighbor returned and asked for another delicious cookie. He told her there were none left and that there was only a finger in the bag. She picked up the bag, saying 'Yes, I know your sense of humor' and thrust her hand into the bag. Her screams when she picked up the human finger could be heard right through the university.

Reuven started out his research at the Institute for Arid Zone Research, which later became part of the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, where he began with goats and mice. He became interested in the camel out of a strong desire to find a solution for the famine in Africa at that time. "The camel was the first animal to be domesticated for its milk, much earlier than the cow," he wrote, "and it can provide an enormous amount of milk, even during droughts. And since there are camels in many places that are suffering from drought, why import food when there is a local solution?"

He began research with one camel, named Golda, published many academic papers internationally, and was filmed for a BBC documentary on the ability of the camel to subsist for long periods of time without drinking any water at all and then drinking 200 liters in a few minutes with no problem, which no human being could do.

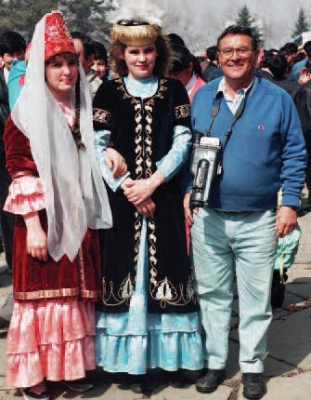

His main breakthrough came when he pioneered methods for in vitro fertilization in camels. In 1986, a book he wrote on the uses and benefits of camel milk was published and translated into Arabic and disseminated in many countries, even those that have no diplomatic ties with Israel. Following the book, Yagil traveled all over the world, and was invited to third-world countries using his vast knowledge to help improve the milk yield of local camels. He visited countries such as Kenya and Ethiopia in Africa for help with their one-humped camels (dromedaries), India, Inner Mongolia and Kazakhstan in Asia for help with their two-humped camels (Bactrian camels) and South America for help with llamas and alpacas. Go'el Drori, a Beer Sheva photographer, joined him in two of those trips. "The first one was in 1994, right after the collapse of the Soviet Union," says Drori. "The first Israeli ambassador to Kazakhstan invited Reuven to consult on camels, and I joined him as a communications consultant. Two years later, he was invited to Ethiopia to consult on nutrition. Everyone already knew of him, everywhere he went he was treated like royalty with immense respect and esteem but he always remained the same down-to-earth, unpretentious person, talking as easily with heads of state as well as with ordinary farmers. He formed immediate rapport with everyone at all levels."

Indeed, anyone who knew Yagil admits he felt just as comfortable in palaces as he did in huts in the middle of the desert; he enjoyed speaking with nomads just as much as he did with academic scholars. "He loved teaching informally," says his daughter, Illana. "Once he brought sheep lungs to my classroom and demonstrated how they expand by blowing into them. He was a man with incredible presence who hated silence. He would talk all the time. I remember driving with him out of town and if the conversation stopped for a moment, he would begin reading the road signs to me. Anything just not to have silence."

Yagil was born and raised in Pretoria, South Africa. As a child he played football (soccer) and dreamt of becoming a professional player. At the age of 20 he met with representatives from the Jewish Agency who fired his enthusiasm about the Zionist dream. In 1955 he came to live in Israel, enlisting in the paratroopers in the Israeli army. As a teenager he had learned to milk cows, and after he finished his military service he worked as a dairy farmer on Moshav Habonim in northern Israel. While there, the regional veterinarian convinced him to study veterinary medicine. He moved with his family to Utrecht, Netherlands to pursue his studies. When he returned, he settled in Beer Sheva and opened a small clinic next to his home, where I got to work when I was young.

This was forty years ago, when schools taught girls to knit and sew. At that time, some breeds of dogs, like Dobermans and Boxers, would have their ears cut to make them stay upright, which was considered beautiful, and Prof. Yagil looked for help with the sewing of the cuts after the surgery. Quite a few people raised an eyebrow when they saw a 12-year-old girl with clamps and a needle suturing their sedated dog's ears. But he would laugh and say that if a girl can sew a shirt, she can sew a dog's ear. Prof Yagil laughed a lot. Once he showed me that he had hidden in the house freezer a neck of a lamb that had two heads growing out of it. When I closed my eyes in disgust, he laughed and made me swear not tell his wife.

Prof. Yagil could have been very rich, but he grew up on the values of the Zionist vision. He never patented his findings or marketed himself. Someone else would have appeared on television and raised funds but Yagil did not use marketing tools, not even those available 40 years ago. It just wasn't in his character. "He wasn't a businessman," agreed his wife. "He had other pioneering ideas that did not catch on, such as soap or baby food from camel milk, but patenting these ideas costs a lot of money and he was told his proposals did not meet patenting criteria." He daughter Illana adds, "Over the years he would give a lot of his knowledge for free to many people. He did not understand that there are unprincipled people who would take his knowledge and open businesses based on what they learned, and that is how his knowledge got a life of its own."

In recent years he was diagnosed with PMR (Polymyalgia rheumatica), an inflammatory disorder, and suffered a great deal of pain. His wife, Bracha, looked after him and cared for him until the day he died. He left behind three children – Illana (60), Tal (59), and Oren (49) – five grandchildren, and four great grandchildren, scores of papers and articles, and countless fans all over the world who will continue to enjoy his discoveries and will never forget him.

Translated from the Hebrew by Oren Yagil

Comments