A Yiddishe Kopf

Swedish Jewish man's cranium finally put to rest . . . 125 years on

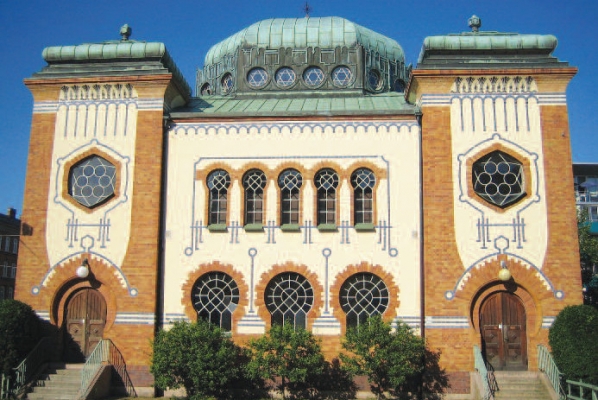

The Swedish city of Malmö has been in the news the last few years, mostly in the light of unpleasant items relating to anti-Semitic acts against the local Chabad Rabbi and other Jews. Some twenty-five per cent of the city's population are Muslim immigrants. Anyone wearing a kippa, Star of David or any other type of Jewish identification is a potential target for these anti-Semitic acts. Occasional stone throwing, graffiti, and fire bombs on the Jewish synagogue and nearby Community Center and at the Jewish burial chapel are not uncommon. In total, over a hundred incidents were reported to the police, who had appointed a special officer to investigate hate crimes but, so far, this has not resulted in any convictions.

The Jewish Community of Malmö is responsible for the smaller communities in southern Sweden, including the university town of Lund, some twenty kilometers north of Malmö.

The cranium of Levin Dombrowsky, a Jewish man in Sweden who committed suicide while in custody in 1879, was buried at Malmö's Jewish cemetery in 2005 in a ceremony attended by representatives of Sweden's parliamentary parties. After his death, Dombrowsky's body was dissected in an anatomy class. His cranium was later tagged "Iudaicus - Jewish in Latin" and added to a collection of human remains used in race biology research. Dombrowsky's cranium was one of hundreds collected by the University of Lund.

The university handed over the cranium to the Malmö Jewish community after the head of Malmö's Chevra Kadisha—Burial Society— discovered it in an exhibition at the museum Kulturenin 2001, and a local newspaper, Sydsvenska Dagbladet, published several articles tracing Dombrowsky's fate. These started with his arrival in Sweden from Filipow, in what is today Poland, to his suicide in 1879 while awaiting trial for theft in Lund.

When the 25-year old Levin Dombrowsky hanged himself in the Lund detention center, few people, if any, cried. Firstly, because he was a Jew and therefore was viewed with great suspicion by many of the locals. Secondly, because he was a thief, suspected of having stolen gold- and silver watches, cash, fabrics, and thirty pounds of human hair (!) from a merchant. The local newspaper's crime reporter described the suicide as if "the roaming Jew Levin Dombrowsky had anticipated the earthly justice".

Thus, Dombrowsky was taken down from his rope and transferred to the Institute of Anatomy, where his body was dissected, already on the following day, in front of a class of medical students. His head was boiled and the cranium was saved.

In the nineteenth century, European researchers traveled the world looking for skeletal remains that they measured and catalogued, often to illustrate the supposed superiority of their own race. Some of the Swedish race biology researchers were also members of a local Nazi group. The University of Lund did not possess a Jewish cranium, so this was a welcome addition to their collection. They now had one thousand, one hundred and two craniums and other skeletal parts which had been collected or exchanged with other academic institutions and archeologists around the world. "Comparative anthropology – comparing craniums between different human races" was a specialty in "race biology" at the Lund University up until the 1940s.

Did the arresting policemen or the anatomists at Lund know if Levin Dombrowsky had a family in Sweden? If they knew, they did not seem to care to find out. The accepted practice at the time was that if someone committed suicide while in the care of the state, his remains belonged to the state and not to his family. But he did have a family. He was not married and had no children of his own, but he had a younger brother and a mother. Only a few years earlier he had been a respected caretaker at a paper mill in the city of Uddevalla, on the west coast north of Gothenburg, close to the Norwegian border.

In December of 1877, the future looked promising for Levin Dombrowsky. He had been in Sweden for six years and approached the Rabbi in Gothenburg, Moritz Wolff, with a request for help in writing a letter to the King. Hardly any other Jews lived in Uddevalla, except for the Jewish peddler Efraim Jacobowsky who had moved there from Gothenburg a few years earlier and opened a small shop. And now Levin Dombrowsky, of course, and his teenage brother—the tailor apprentice Kain Dombrowsky.

Levin Dombrowsky worked at the press at the Munkedal Paper Mill and his behavior was exemplary. He was soon promoted to office caretaker with a monthly salary of sixty Swedish crowns. This was the time to invest in a future life in Sweden. In December of 1877 he wrote to King Oscar II:

"The undersigned, who immigrated hereto, six years ago from my fatherland Russian Poland, to Your Royal Majesty's country Sweden, hereby, in deepest submissiveness, asks for the mercy of your Royal Majesty for me in the kingdom to sojourn."

He signed the letter "Your Royal Majesty's most humble and faithful minion, Levin Dombrowsky."

The management of the Munkedal Paper Mill certified that he "in a resolute, unassailable, and diligent manner performed his duties and had exhibited exemplary behavior.".

Levin Dombrowsky's application to remain in the country is a bit strange. He did not, in fact, need such a residence permit.

Up until 1870, Jews were only allowed to settle in four cities: Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malmö, or Norrköping. Their civil rights were severely curtailed. But, in 1870 the laws were alleviated. As long as the Jews supported themselves and paid taxes, the authorities did not interfere in what they were doing.

Did Levin Dombrowsky still want to have some sort of certificate, some document that he was Swedish? Maybe the employer, Munkedal Paper Mill, demanded it? In any case, he received his permit and immediately submitted another application, this time requesting to become a Swedish subject.

Like many other East European Jews, Levin Dombrowsky's mother tongue was Yiddish. When he grew up in the small town Filipow, in what is now eastern Poland, near the borders of Lithuania and Belarus, he had only learnt to write in Hebrew letters. He could not read or write Swedish and spoke with a broken accent.

His father's name was Jacob and he was the owner of a bath house in Filipow. The father died in 1864, when Levin was only ten years old, and is probably buried in the Jewish cemetery which still exists in Filipow. His mother was called "Wedda" or "Hedda" in the Swedish documents. Levin's younger brother, as mentioned earlier, was called "Kain" (which was probably a misnomer for Chaim, Haim or Khaim; no Jew in Eastern Europe would name his son Kain).

In 1871, when Levin was seventeen years old, he fled from Filipow. He was afraid of being drafted into the Russian Army, a twenty-five-year-long "virtual imprisonment." He traveled to Königsberg – today's Kaliningrad – and caught a boat to Copenhagen. He then continued to Sweden and Gothenburg, where he had some acquaintances and where there was an existing Jewish community. In Malmö, where a few hundred Jews were living, the Jewish Community would be established only in December of 1871.

Levin Dombrowsky's mother and brother Kain joined Levin in Sweden. They settled in the small coastal community of Fjällbacka, where Dombrowsky, during his teenage years, supported his family as a peddler.

One day in 1874, Dombrowsky, by then a twenty-year old, arrived with his goods at Uddevalla and the Munkedal Paper Mill. The management was desperately looking for more workers and on the spot offered him employment.

After two years – "first at the machine and later at the press" – he was promoted to office caretaker. But when the director of Munkedal, around Easter 1878, wanted to lower his monthly salary from 60 to 45 cr., Levin Dombrowsky quit.

Levin, who at the time lived together with Kain, was planning to peddle goods again. His initial capital was 150 cr.; he had saved 90 cr. and received an additional 60 cr. in severance pay. But something must have gone wrong.

In August of 1878, Levin Dombrowsky was arrested for theft. He was suspected of having stolen money and goods from the merchant Efraim Jacobowsky. The Jacobowsky shop was short of 350 cr. in cash, corduroy fabric with a value of 90 cr., seven pairs of underwear as well as a box of cigars.

All the goods were found at the home of Levin Dombrowsky who, however, denied the charge. Someone must have put the stolen goods in his apartment "as a spectacle," he claimed at the Uddevalla court house.

The judge didn't believe him, urging him instead to "speak the truth and confess to the crime".

He was sentenced against his denial to four months of hard labor for "first time theft". He was not expelled from Sweden, but during a five-year period would "forfeit his civil rights".

Levin Dombrowsky served his time in the Uddevalla Detention Center. Nothing much was noted in the prison logs, except that he was released and transferred to Gothenburg on February 4, 1879.

Following the prison time, Levin Dombrowsky seems to have been roving around for several months. He was disgraced in Uddevalla and could not remain there. Half a year later he was arrested in Malmö, suspected of having stolen goods worth 2000 cr. from the Lund merchant Nils Lewin. He sometimes used the family name Jakobsson and stayed at a hotel in Malmö.

Since he was suspected of having committed a crime in Lund, he was transferred from Malmö to custody in Lund. On September 25, 1879, Levin Dombrowsky was scheduled to be arraigned at the court house in Lund. He pleaded not guilty, but the police were sure they had convincing evidence. He had hidden the stolen goods at various places in Lund, among other locations "in the attic of a Jew (living) on Grönegatan".

A lingonberry merchant who was Dombrowsky's neighbor at the hotel testified that Dombrowsky had asked him to hide stolen gold watches and hair. The merchant also identified him in a line-up.

The day of the trial was two days before Yom Kippur. Some people speculate that he had asked to be able to attend prayers on Yom Kippur and when this was denied, he became suicidal.

Nobody had heard anything when he hanged himself – the night Levin Dombrowsky died, he was the only prisoner in the arrest cells.

Levin Dombrowsky's cranium was buried one hundred and twenty-five years after his death. The head of the Malmö Chevra Kadisha, Helmer Fischbein, who had led the struggle to give Levin Dombrowsky a proper Jewish burial, concluded:

"The decision reinstates Levin Dombrowsky's dignity, and at the same time reinstates the dignity of the University of Lund. The time has come to put the race biology behind us."

Acknowledgements:

The facts are based on articles in the Swedish newspaper Sydsvenskan in 2005 and 2010 and on private correspondence with Helmer Fischbein, the head of the Malmö Chevra Kadisha.

Comments