A Requiem for Chayym

My present career as a "journalist" began when Esra Magazine editor, Merle Guttmann, asked me to interview Chayym Zeldis for the September 2003 issue. I was told that he was an internationally known novelist and poet who, rather than spending his summers hiding out at the Hamptons, partying on Martha's Vineyard or living in sullen seclusion on a remote New Hampshire farm, resided year-round in Ra'anana, not far from my own address. I had been a writer of one sort or another for several years — academic articles and monographs, essays, short stories, even a poem — but I had never interviewed anyone for a newspaper or magazine article. Nor was I particularly well-prepared for this, my first time at bat. I had neither read anything that Chayym had written nor had even the vaguest idea of what he looked like when I entered the small, noisy Ahuza Street café in which we were to meet. Even so, the experience was a smashing success, through virtually no effort or talent of mine.

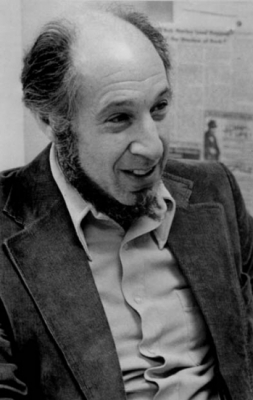

The café was full to bursting when I timidly walked in — so nervous I wanted to genuflect (never an encouraging sign when performed by Jews), but I recognized Chayym at once. Amidst the eating, drinking, smoking, ash flicking, coffee stirring, gesturing, posturing, posing, schmoozing, kibitzing and screaming going on from one end of the place to the other, there sat one man with eyes bright and alive, taking everything in, enjoying every sound and movement going on around him, studying people, gaining new insights and somehow doing all of this without either succumbing to voyeurism or hiding behind a pose of analytic detachment. Here was a fellow, obviously somewhat along in years, sitting in a crowded café to watch a wonderful human comedy of which he knew he was an inextricable part.

Chayym watched with an amused but kind forbearance as I fumbled for a moment with my backpack, tape recorder, camera, notebook, pen, pencil and cup of coffee, and then proceeded to tell me about being a writer. I quickly came to understand that writing was not about backpacks, tape recorders, cameras, notebooks, pens, pencils or even coffee, but rather about curiosity, observation and sharing. He told me, "The Talmud says that anywhere you look, there's something to see. I think that that's what's at the core of a writer. Everywhere he looks, there's something that interests him, something to see, something to figure out, something to first share with himself and then share with other people." He also explained that writers can never really detach themselves from whatever it is they are writing about. "Writers write about people," he said, "but in a way they also almost always write about themselves. Often it's without knowing it — it's not self-consciously autobiographical. But when they're writing about people, they're really writing about their own reactions to people, to experiences, to life and to what life means to them."

I don't recall whether or not I actually asked many questions that day. I think I mostly let him talk while the tape recorder rolled. I do recall Chayym giving me a pointed bit of advice as the two hour or so "interview" drew to a close. He said to me, "Long ago I worked on a kibbutz. My job was to milk cows. And I learned that if you milk every day, you get more and more milk. If you stop milking, the milk dries up. It's the same with writing. If you don't milk your subconscious every day, you're not going to get anything." He told me to make certain to set aside some time every day for writing. "I needed to do this," he said, "to think, feel, wonder and, most importantly, keep the words flowing."

After Chayym excused himself and left to teach his creative writing class at Tel Aviv University, I sat in the café for an hour, mentally and physically exhausted, just trying to absorb some of the ideas that had been thrown at me for the past couple of hours. I went home, read Chayym's novel, The Geisha's Granddaughter, which the local magazine had also asked me to review, and soon discovered why internationally acclaimed author Jerzy Kosinski had called him "a masterful novelist," why Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Richard Rhodes said his novel Brothers was "monumental", why Elie Wiesel, discussing his novel The Brothel, said that 'his knowledge of history is as amazing as his skill in using it' and that his novel The Geisha's Granddaughter sings 'with a melody that seems to come from new depths'. I could only agree with novelist Henry Miller, who said Chayym's writing has a "magical quality…very strong, very compelling".

I never thought I'd see him again. Established, highly acclaimed authors do not normally welcome the company of new, totally obscure writers. Not long after my article on him appeared, however, I heard his unmistakable voice over my mobile phone one bright morning, suggesting we get together for coffee. This invitation was to establish a pattern that persisted for the next five years, right up to just a few days before Chayym's unexpected death. He and I would get together every couple of months, drink coffee, give each other some of our respective stuff to read, and talk about writers and writing.

Well, to tell the truth, for most of the time he talked and I listened. The man was a living, breathing encyclopedia of 20th Century writers — not to mention publishers, editors, book reviewers and even literary agents. He seemed to have known virtually everyone in contemporary literature at some time or another, and his anecdotes were fascinating, often hilarious. The only topic he was guarded about was the subject of Chayym Zeldis himself. After God knows how many lengthy sessions in cafes; after getting to know Nina, his wife, companion and muse; after meeting his two daughters and, of course, reading all of his books, I realize now how little about his personal life I really know. I don't even know how old he was. "Let's just say I'm somewhere in my seventies," he told me during that first interview. In point of fact, Chayym was ageless, driven by an almost childlike curiosity about the world around him, blessed with a youthful openness to different opinions and new ideas, and gifted with a wisdom as old as mankind.

I believe that his last several years were a frustrating time for Chayym. Being a writer, it seemed, was both more complicated and a lot less fun in 2008 than it had been a half-century before. The world's declining literacy and overall "dumbing down" were not making it easy to get new books published and read. In a little speech that I delivered at his funeral — one of many heartfelt speeches recited at his graveside on that day — I lamented that Chayym had been writing novels in a world where people weren't reading anymore, along with poetry during a time in which people's hearts and souls have forgotten how to sing.

Yet in the final analysis, none of that really mattered to Chayym. He was, quite simply, driven to write. Writing was his raison d'etre, his mission, his life. Not writing was not an option. Chayym Zeldis wrote, as he told me many times, because he had to.

Comments