The Madwoman In The Rabbi's Attic - Review

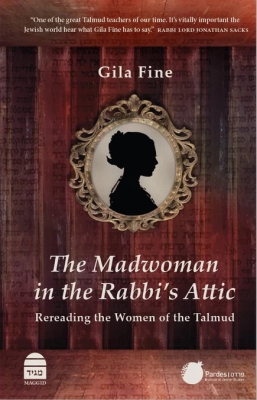

The Madwoman in the Rabbi's Attic: Rereading the Women of the Talmud

Gila Fine

Maggid

288 pages, $30

Reviewed by Pamela Peled

Romeo and Juliet manage one stolen night of wedded bliss before the young Montague flees to Mantua and it's all downhill from there; theater goers have long luxuriated in the "love conquers all" mantra of the much-loved play. But recent feminist critics have ripped into that sacred, too-short marriage, closely reading the dawn scene for proof. The nightingale that Juliet hears, singing on yon pomegranate tree, they claim, has symbolic, mythological overtones of rape and hell; the birdsong that "pierces the fearful hollow of her ear" is a metaphor for sexual violation. Just like that Romeo becomes a rapist; Juliet an unwilling victim in a brutal night.

You can agree with the interpretation or not, but the argument is anchored in the text and definitely presents a fresh perspective. In similar fashion Gila Fine, acclaimed Talmudic scholar and adored teacher, has done a delicious job deconstructing the stories of six women who sparkle in the Talmud, putting their characters into context, closely reading their short cameo appearances, and shattering their anti-feminist stereotypes that have leered at rabbinic literature learners for centuries.

Fine's delightful The Madwoman in the Rabbi's Attic is written with such a light touch as it dishes up Greek mythology and medicine, midrashim, modern movies and everything in between. This seemingly esoteric book is more compelling than any novel. I could not put it down.

The title references Mr. Rochester's lunatic wife, Bertha Mason, locked up in the attic of the grand house in which Jane Eyre is employed as governess. The Madwoman in the Attic was a 1979 breakthrough book by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar examining Victorian literature from a feminist perspective; Fine's Rabbi's Attic provides the space for her eagle-eyed research into Talmudic females.

Every line of this bubbly book contains titbits of information that make life worth living: did you know that there are over a thousand named men in rabbinic writings, but only fifty-two women? Most Talmudic gals are notoriously anonymous – the 'wife of,' or 'daughter/sister/mother of' … the she who must not be named. Fine does not shy away from the traditional Talmudic attitude to the fairer sex: "When woman was created, the Devil was created with her" grimaces some rabbinical authority (Genesis Rabba 17:7); Fine acknowledges that woman was the conventional mother of all vice.

Fine, who is careful not to show any disrespect to religious scholars, nor to question the authority of Talmudic rabbis, points out that umpteen generations of devout bochers in traditional Yeshivas never studied the few stories of women in the Talmud; had they done so I guess they would not have reached her conclusions. She convincingly, however, makes the case that a close reading of the vignettes about wives and widows with nomenclatures reveals that the primal rabbis might not have been proto-feminists, but neither were they necessarily patriarchal puritans. Fine is not too fussed about pulverizing preconceptions; through close focus on the text she sheds a gentle light on the luscious little stories so readers can draw conclusions of their own.

Her methodology is magnificent: each of the six named females in the Talmud are presented as archetypes: Yalta the shrew, Homa the Femme Fatale, Marta the Prima Donna, Heruta the Madonna/Whore, Beruria the Overreacherix, and Ima Shalom the Angel in the House.

Each archetype is explored from all conceivable angles: Greek mythology, rabbinic literature, the Bible, medieval folktales, modern plays, 20th Century film. She then walks us through a primary reading of the terse Talmudic tale, and explains it on the literal level.

Chapter one has Rabbi Ulla paying a visit to Rav Nachman's happy home. Ulla eats, says Grace after meals, and hands the cup of blessing to his host, whereupon Nachman requests that Ulla also send the cup to Yalta, his wife, (who presumably planned the menu with her cook). Ulla refuses, citing scripture to claim God only blesses man's body, not woman's. Yalta hears, has a hissy fit, and proceeds to the wine storehouse to smash four hundred jars of wine. Rav N. begs his guest to send her another cup; Ulla accedes but includes a castigating message to his hostess, who replies that "gossip comes from peddlers and lice from rags". (Berakhot 51b).

Fine revisits this seemingly clear indictment of vicious women who can't control their emotions; and turns the story on its head. Through comprehensive analysis of other Talmudic passages where Yalta appears (Fine really, really knows her Talmud), she proves that the woman was learned, reasonable and a fitting helpmate to her husband.

A fascinating exploration of Aeschylus and Aristotle's conclusions about human procreation and reproduction reveals that current theories claimed that man, who mounts, begets; women are passive vessels inside whom the male seed is incubated.

So, when Yalta hears that as a receptacle she doesn't deserve to be blessed, she determines to break a goodly quantity of other vessels, to see how that goes down with the men and masters. Look, she is saying as she hurls earthenware jars in all directions: what good is wine without something in which to store it?

At the end of the chapter Fine delivers the moral: Yalta's tale is not a petty fight over a cup of wine, but a principled debate about the power of procreation and women's reproductive worth (and their right to its blessing).

Fine does not claim that Femme Fatales were not fatal but fabulous, and that Shrews were honeys deep down, but it might still be a bit of a stretch for many readers to believe that, through their tales, the rabbis were providing readers down the ages with a subtle suggestion never to dismiss the Other, but to closely cull all hints and hidden signposts implying that this Other is not so threatening after all. Still, Fine's fabulous, scholarly, intriguing book certainly makes a convincing case for revisiting and revising blanket assumptions.

I'm going to start reading it all over again; it's the best 'impress-your-friends-with-your-esoteric-Talmudic-knowledge' that you could ever read. Rush to get your copy!

Comments